African art has had a place at the Museum of Modern Art from its earliest days — though not the African art you might think. In 1935, back when the museum nestled into a townhouse on West 53rd Street, the curator James Johnson Sweeney organized “African Negro Art,” whose 600 specimens included Dogon painted masks, Baoulé ivories and bangles and Congolese seats and spoons. It was one of the most popular exhibitions of MoMA’s first decade, and toured the United States.

Art Review

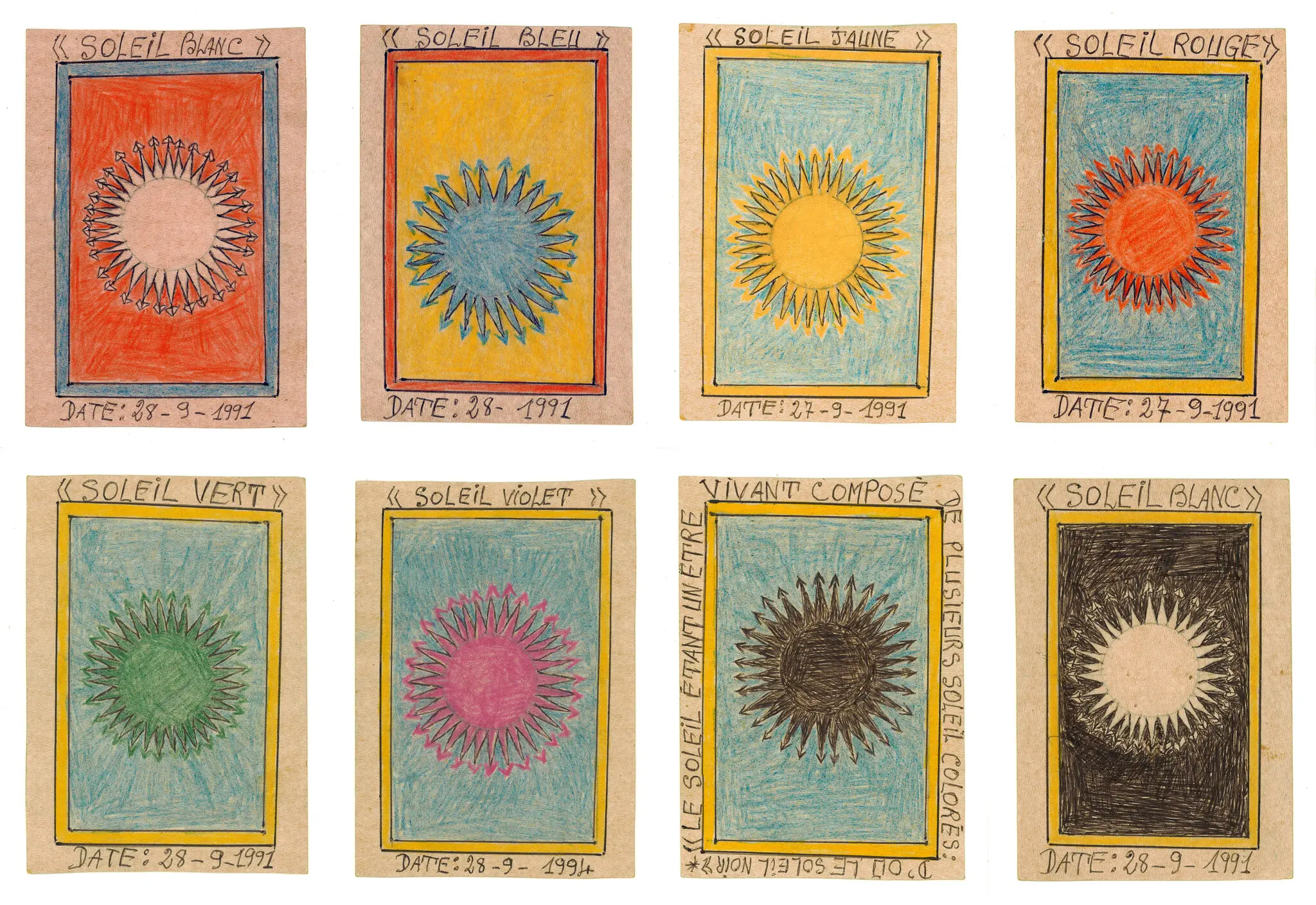

The African Artist-Writer Who Mapped New Worlds

In 1948, Frédéric Bruly Bouabré had a vision that led him to invent a new writing system. The Museum of Modern Art explores his more than 1,000 drawings.

- Share full article

By Jason Farago

March 31, 2022

African art has had a place at the Museum of Modern Art from its earliest days — though not the African art you might think. In 1935, back when the museum nestled into a townhouse on West 53rd Street, the curator James Johnson Sweeney organized “African Negro Art,” whose 600 specimens included Dogon painted masks, Baoulé ivories and bangles and Congolese seats and spoons. It was one of the most popular exhibitions of MoMA’s first decade, and toured the United States.

Why were they at MoMA, and not a museum of ethnography or anthropology (or, worst of all, natural history)? Because, Sweeney maintained, these ritual objects were in fact modern art — the best modern art of the age, in fact. “As a sculptural tradition in the last century,” Sweeney proclaimed, “it has had no rival.”

Why were they at MoMA, and not a museum of ethnography or anthropology (or, worst of all, natural history)? Because, Sweeney maintained, these ritual objects were in fact modern art — the best modern art of the age, in fact. “As a sculptural tradition in the last century,” Sweeney proclaimed, “it has had no rival.”

Yet if MoMA could turn these objects — notably pillaged Benin bronze plaques, which the curators borrowed from German ethnographic museums — into “modern” sculpture, the anonymous Africans who made them certainly did not become “modern artists.” Even by the 1980s, with the museum’s notorious “‘Primitivism’ in 20th Century Art,” the African masks and statues that stood alongside Gauguin and Picasso were purged of their historical, legal and religious significance, without even an indication of when they were made. Only in 2002, when the Nigerian curator Okwui Enwezor brought his sweeping exhibition “The Short Century” to MoMA PS1, would living African artists enter the museum, names known and on equal footing with their Western counterparts.

Image